The Quiroste

The Quiroste’s home territory encompassed roughly 90 square miles and stretched from the sea to ridge-tops in the mountains to the east. Like their neighbors, they spoke a language in the Ohlone group; and they were hunters and gatherers who knew how to manage their land’s resources so that the plants upon which they relied would proliferate. As we shall see, one of their most important management tools was fire.

The Quiroste first appear in written history in 1769 when they welcomed Gaspar de Portolá’s overland expedition of Spanish soldiers and clergymen into their village, which the natives called Metenne. Portolá estimated the number of inhabitants as 200, but he wrote little else. Miguel Costansó, however, provided a fuller account in his journal entry for October 23rd:

“We shifted camp … close to a heathen village which had been discovered by the scouts, and situated in a pleasant pretty spot at the foot of the mountains, opposite a gorge covered with pine-trees and savins, among which ran down a stream of which the Indians availed themselves. The land, covered with grasses and nowise scant of wood, was plainly well-favored.

“The heathens, who had been warned by the scouts of our coming to their lands, received us with a great deal of affability and kindness, nor failed to make the usual present of seeds kneaded into thick dough-balls; they offered us also bits of honeycomb of a kind of syrup which some said was wasp-honey: they brought it elaborately wrapped up between cane-grass leaves, and its flavor was not to be despised.

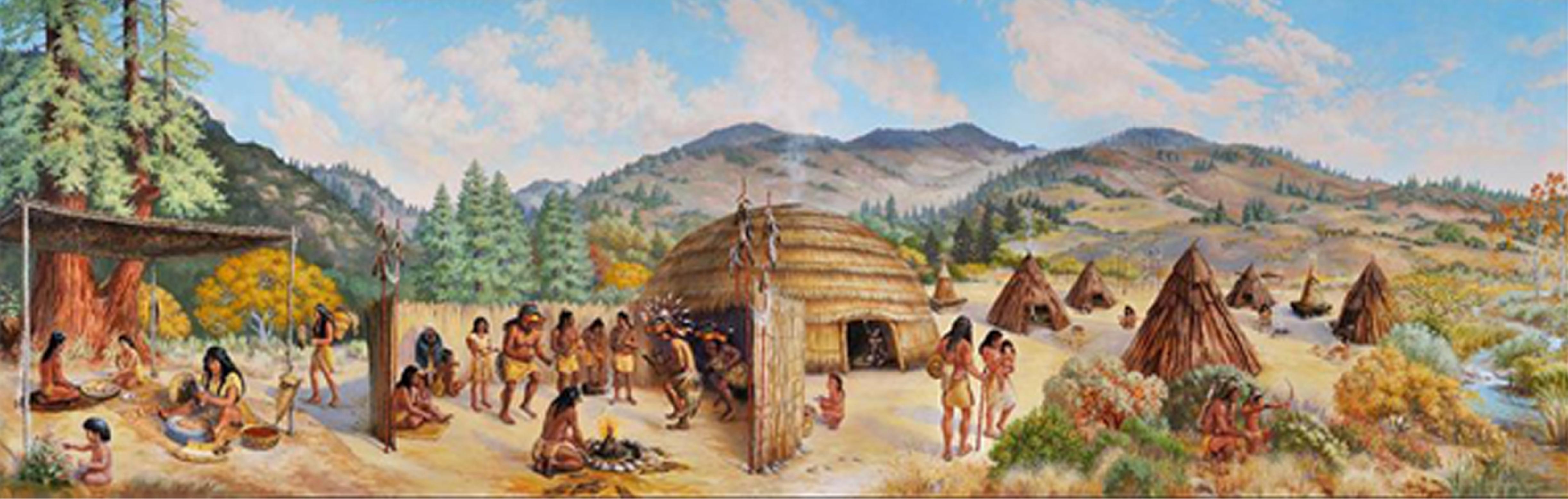

“In the midst of the village there was a great house of spherical shape, very roomy; while the other little houses, which were of pyramidal form and very small-sized, were built of pine splints. And because the big house stood out so above the rest, the village was so named [Rancheria de la Casa Grande or Big House Village].”

—Journal of Miguel Costansó, translated by Alan K. Brown [1]

The Spanish soon returned to Alta California to stay, of course. The later history of the Quiroste is an unhappy one. They avoided the Spanish missions until 1791, when their leader “Charquin” was baptized at Mission Dolores. Soon disenchanted, he fled the mission a week later; and the Quiroste began harboring fugitives from the mission system. He was captured by the Spanish in 1793 when the Quiroste attacked Mission Santa Cruz. In the following year most of the remaining Quiroste people entered Mission Santa Clara; and as a result of European diseases, hardship and death in the missions, their identity as a separate people was lost. Today no Native Americans are known to identify themselves specifically as Quiroste. (Today’s Ohlone people are the direct descendants of the combined tribal populations that mixed in the missions.)

By the 1820s the Spanish were herding cattle in and near Quiroste Valley. By the early 1900s it was part of the Steele family’s dairy farm. Still later, the land was acquired by a developer but then sold in the 1980s to California State Parks. State Parks’ mission in part is to preserve cultural history. While all agriculture was removed, the land’s acquisition came some 40 years too late to preserve at least one cultural trove. It’s known that in the 1940s a farmer bulldozed a 5-ft mound of artifacts.

Research begins in Quiroste Valley

California State Parks archaeologist Mark Hylkema relates the beginning of archaeological research in the valley:

“Research began in 1982 when I first surveyed it and recorded over a dozen prehistoric archaeological sites. Later in 2004, I sponsored Cabrillo College to conduct test excavations there over two summers. I then submitted three radiocarbon dating samples to inform of us as to whether or not this might be the site of the Casa Grande. The dates corroborated that temporal setting. Later, the Amah Mutsun were introduced to the valley after one of their tribal members, Chuck Striplen, was alerted to it as a potential place to do his Ph.D. studies. This brought in the interests of both his tribe and the UC Berkeley Dept. of Anthropology, which began their investigations in 2007.”

In 2008 California State Parks created the Quiroste Valley Cultural Preserve. Now as then, Hylkema in particular, as Santa Cruz District Archaeologist, and California State Parks in general continue as the driving forces behind and overseers of research and collaboration in the valley.

An Example Research Program

The Quiroste Valley Cultural Preserve was created to protect cultural resources, to restore native vegetation, and to re-implement “traditional resource and environmental management.” (The archaeologists shorten this phrase into the acronym TREM.)

These management practices are known to include pruning, tending, and selective burning. While pruning and tending useful plants is only logical, the Natives’ use of fire may be generally less well known—yet it was practiced widely. Fire cleared land of trees and shrubs and opened it to desirable grasses. The journals of the Portolá Expedition described mile after mile of coastal grasslands that showed evidence of recent fires.

Among the valley’s researchers, for example, is Dr. Rob Q. Cuthrell, postdoctoral scholar at the Archaeological Research Facility at UC Berkeley, who received a grant from the National Science Foundation for a three-year study of TREM in the greater San Francisco Bay Area. In one example of his research, he and his colleagues found high densities of microscopic remains of grasses and sedges called “phytoliths” to a depth of 45 cm in all 7 of the sample locations they excavated in Quiroste Valley. These findings indicate the presence of grasslands over the long term. In one of these locations, the high density of phytoliths continued to a depth of one meter, and the deepest were dated from the 5th Century. The archaeological and environmental data analyzed by the research team suggested that the frequency of fires far exceeded what would be expected solely as a result of lightning strikes. These efforts and other research lead him to conclude: “Eco-archaeological research shows that the Quiroste and their ancestors likely managed coastal landscapes using fire for at least 1000 years, and possibly much longer. They burned the landscape frequently to maintain extensive areas of grassland that provided reliable and productive food sources.”

Over the nine years since the establishment of the Quiroste Valley Cultural Preserve, a team of two-dozen or so scientists and researchers from California State Parks, UC Berkeley, UC Santa Cruz, and other institutions and—significantly and valuably—members of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band have collaborated and are still collaborating in studying the valley.

The Amah Mutsun

Before the mission era, the Amah Mutsun lived in an area extending eastward from the mouth of the Pajaro River and centered about present-day Hollister. Today nearly 600 people are enrolled members as documented, direct descendents of the native people who were subsumed by Mission San Juan Bautista and who were called the “San Juan Band” by the precursor to today’s Bureau of Indian Affairs.

While their language is also classed as one of the eight in the Ohlone group, each language differs substantially from the others—“as different from one another as Spanish is from French” in Romance languages, according to the tribe’s website. Their religious practices, hunting and fishing methods, and so on were in many cases different from their neighbors. Nonetheless, their traditional resource and environmental management practices are believed to be not unlike those of the Quiroste. Their collaboration in Quiroste Valley gives the archaeologists valuable insights, and it gives the tribe a place to practice land management as their ancestors did, as informed by the scientists’ findings, and to teach their next generation.

Dr. Cuthrell is among the scientists associated with their involvement. In a slide presentation he gave to a group of State Parks volunteer docents a few months ago, he described the tribe’s efforts:

“In a research project largely initiated by tribal members, they seek to answer these questions:

- Which biotic resources were used?

- How could they have been managed?

- How to practice TREM today?

“The Amah Mutsun Land Trust was created in 2012 to reconnect tribal members with landscape stewardship and traditional cultural knowledge… . The primary program of [the trust] is the Native Stewardship Corps, which provides immersive landscape stewardship fieldwork experiences for tribal members.”

He went on to describe several of the many projects the corps has undertaken in local state and national parks, including this list of accomplishments specifically in Quiroste Valley:

- recorded botanical and ethno-botanical information on 30-40 native plants;

- tended a stand of ceremonial plants and tripled their number

- harvested and used native grass seeds, yerba buena, elderberry, buckeye, berries, and others;

- removed encroaching woody vegetation in 10-12 acres of coastal prairie;

- removed over 20,000 poison hemlock plants from the valley;

- recorded locations of ethno-botanical resources and created a Google Earth map with the data.

Future Plans

Preservation and restoration of the valley’s cultural heritage are paramount. Native plants are gradually returning to Quiroste Valley and non-native and invasive plants are being painstakingly removed. The transition to a state similar to what existed 300 years ago will take many more years. At some point, when landscape conditions are suitable, fire may once again be used in a controlled burn to manage the landscape. But most assuredly there will be no more bulldozers.

Acknowledgements:

Ann Thiermann has graciously granted permission to CSPA to use an image of her extensively researched mural “Dancing at Quiroste.” To see images of more of her art, to learn where you will find some of her murals, and to learn more of this artist, muralist and educator, visit her website at AnnThiermann.com.

A significant part of the information in this article was taken directly from Dr. Cuthrell’s slide presentation mentioned above. We are most grateful to him for his permission to share it with CSPA’s readers.

Suggestions for further reading: (by either Rob Cuthrell or Mark Hylkema)

Omer C. Stewart, Forgotten Fires: Native Americans and the Transient Wilderness, work completed 1954, published 2002.

M. Kat Anderson, Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources, 2005.

Kent G. Lightfoot and Otis Parrish, California Indians and Their Environment: An Introduction, 2009.

Hylkema, Mark and Rob Cuthrell, "An Archaeological and Historical View of Quiroste Tribal Genesis," Journal of California Archaeology, Vol 5, No 2, pp. 224-244, 2013

Reference:

[1] F. Boneu Companys, Gaspar de Portolá: Explorer and Founder of California, Instituto de Estudios Ilerdenses, Lerida, Espania, 1983. Translated and revised by Alan K. Brown.